Language family of the Andes in South America

| Quechuan | |

|---|---|

| Qichwa/Qhichwa, Kichwa, Runa Simi | |

| Geographic distribution | Throughout the central Andes Mountains including Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. |

| Ethnicity | Quechua |

Native speakers | 7.2 million[1] |

| Linguistic classification | One of the world's primary language families (or Quechumaran?) |

| Subdivisions | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | qu |

| ISO 639-2 / 5 | que |

| ISO 639-3 | que |

| Glottolog | quec1387 |

Map showing the distribution of Quechuan languages | |

Map showing the current distribution of the Quechuan languages (solid gray) and the historical extent of the Inca Empire (shaded) | |

| Person | Runa / Nuna |

|---|---|

| People | Runakuna / Nunakuna |

| Language | Runasimi / Nunasimi |

Quechua (,12 Spanish: [ˈketʃwa]), also called Runa simi (Quechua: [ˈɾʊna ˈsɪmɪ], ‘people’s language’) in Southern Quechua, is an indigenous language family that originated in central Peru and thereafter spread to other countries of the Andes.3456 Derived from a common ancestral “Proto-Quechua” language,3 it is today the most widely spoken pre-Columbian language family of the Americas, with the number of speakers estimated at 8–10 million speakers in 2004,7 and just under 7 million from the most recent census data available up to 2011.8 Approximately 13.9% (3.7 million) of Peruvians speak a Quechua language.9

Although Quechua began expanding many centuries before345106 the Incas, that previous expansion also meant that it was the primary language family within the Inca Empire. The Spanish also tolerated its use until the Peruvian struggle for independence in the 1780s. As a result, various Quechua languages are still widely spoken today, being co-official in many regions and the most spoken language lineage in Peru, after Spanish.

The Quechua linguistic homeland may have been Central Peru. It has been speculated that it may have been used in the Chavín and Wari civilizations.11

Quechua had already expanded across wide ranges of the central Andes long before the expansion of the Inca Empire. The Inca were one among many peoples in present-day Peru who already spoke a form of Quechua, which in the Cuzco region particularly has been heavily influenced by Aymara, hence some of the characteristics that still distinguish the Cuzco form of Quechua today. Diverse Quechua regional dialects and languages had already developed in different areas, influenced by local languages, before the Inca Empire expanded and further promoted Quechua as the official language of the Empire.

After the Spanish conquest of Peru in the 16th century, Quechua continued to be used widely by the indigenous peoples as the “common language.” It was officially recognized by the Spanish administration, and many Spaniards learned it in order to communicate with local peoples.12 The clergy of the Catholic Church adopted Quechua to use as the language of evangelization. The oldest written records of the language are by missionary Domingo de Santo Tomás, who arrived in Peru in 1538 and learned the language from 1540. He published his Grammatica o arte de la lengua general de los indios de los reynos del Perú (Grammar or Art of the General Language of the Indians of the Kingdoms of Peru) in 1560.1314 Given its use by the Catholic missionaries, the range of Quechua continued to expand in some areas.

In the late 18th century, colonial officials ended the administrative and religious use of Quechua. They banned it from public use in Peru after the Túpac Amaru II rebellion of indigenous peoples.7 The Crown banned “loyal” pro-Catholic texts in Quechua, such as Garcilaso de la Vega’s Comentarios Reales.15

Despite a brief revival of the language immediately after the Latin American nations achieved independence in the 19th century, the prestige of Quechua had decreased sharply. Gradually its use declined so that it was spoken mostly by indigenous people in the more isolated and conservative rural areas. Nevertheless, in the 21st century, Quechua language speakers number roughly 7 million people across South America,8 more than any other indigenous language family in the Americas.

As a result of Inca expansion into Central Chile, there were bilingual Quechua-Mapudungu Mapuche in Central Chile at the time of the Spanish arrival.1617 It has been argued that Mapuche, Quechua, and Spanish coexisted in Central Chile, with significant bilingualism, during the 17th century.16 Alongside Mapudungun, Quechua is the indigenous language that has influenced Chilean Spanish the most.16

Quechua-Aymara and mixed Quechua-Aymara-Mapudungu toponymy can be found as far south as Osorno Province in Chile (latitude 41° S).181920

In 2017 the first thesis defense done in Quechua in Europe was done by Peruvian Carmen Escalante Gutiérrez at Pablo de Olavide University (Sevilla).[citation needed] The same year Pablo Landeo wrote the first novel in Quechua without a Spanish translation.21 A Peruvian student, Roxana Quispe Collantes of the University of San Marcos, completed and defended the first thesis in the language group in 2019; it concerned the works of poet Andrés Alencastre Gutiérrez and it was also the first non-Spanish native language thesis done at that university.22

Currently, there are different initiatives that promote Quechua in the Andes and across the world: many universities offer Quechua classes, a community-based organization such as Elva Ambía’s Quechua Collective of New York promote the language, and governments are training interpreters in Quechua to serve in healthcare, justice, and bureaucratic facilities.23

| This section needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (February 2023) |

|---|

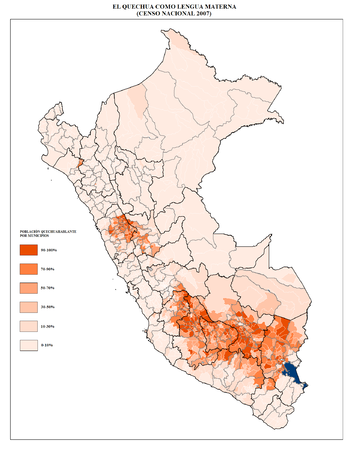

Map of Peru showing the distribution of overall Quechua speakers by district

In 1975, Peru became the first country to recognize Quechua as one of its official languages.24 Ecuador conferred official status on the language in its 2006 constitution, and in 2009, Bolivia adopted a new constitution that recognized Quechua and several other indigenous languages as official languages of the country.25

The major obstacle to the usage and teaching of Quechua languages is the lack of written materials, such as books, newspapers, software, and magazines. The Bible has been translated into Quechua and is distributed by certain missionary groups. Quechua, along with Aymara and minor indigenous languages, remains essentially a spoken language.

In recent years, Quechua has been introduced in intercultural bilingual education (IBE) in Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador. Even in these areas, the governments are reaching only a part of the Quechua-speaking populations. Some indigenous people in each of the countries are having their children study in Spanish for social advancement.26

Radio Nacional del Perú broadcasts news and agrarian programs in Quechua for periods in the mornings.

Quechua and Spanish are now heavily intermixed in much of the Andean region, with many hundreds of Spanish loanwords in Quechua. Similarly, Quechua phrases and words are commonly used by Spanish speakers. In southern rural Bolivia, for instance, many Quechua words such as wawa (infant), misi (cat), waska (strap or thrashing), are as commonly used as their Spanish counterparts, even in entirely Spanish-speaking areas. Quechua has also had a significant influence on other native languages of the Americas, such as Mapuche.27

It is difficult to measure the number of Quechua speakers.8 The number of speakers given varies widely according to the sources. The total in Ethnologue 16 is 10 million, primarily based on figures published 1987–2002, but with a few dating from the 1960s. The figure for Imbabura Highland Quechua in Ethnologue, for example, is 300,000, an estimate from 1977.

The missionary organization FEDEPI, on the other hand, estimated one million Imbabura dialect speakers (published 2006). Census figures are also problematic, due to under-reporting. The 2001 Ecuador census reports only 500,000 Quechua speakers, compared to the estimate in most linguistic sources of more than 2 million. The censuses of Peru (2007) and Bolivia (2001) are thought to be more reliable.

- Argentina: 900,000 (1971)

- Bolivia: 2,100,000 (2001 census); 2,800,000 South Bolivian (1987)

- Chile: few, if any; 8,200 in ethnic group (2002 census)

- Colombia: 4,402 to 16,00028

- Ecuador: 2,300,000 (Adelaar 1991)

- Peru: 3,800,000 (2017 census29); 3,500,000 to 4,400,000 (Adelaar 2000)

Additionally, there is an unknown number of speakers in emigrant communities.30

The four branches of Quechua: I (Central), II-A (North Peruvian), II-B (Northern), II-C (Southern)

There are significant differences among the varieties of Quechua spoken in the central Peruvian highlands and the peripheral varieties of Ecuador, as well as those of southern Peru and Bolivia. They can be labeled Quechua I (or Quechua B, central) and Quechua II (or Quechua A, peripheral). Within the two groups, there are few sharp boundaries, making them dialect continua.

However, there is a secondary division in Quechua II between the grammatically simplified northern varieties of Ecuador, Quechua II-B, known there as Kichwa, and the generally more conservative varieties of the southern highlands, Quechua II-C, which include the old Inca capital of Cusco. The closeness is at least in part because of the influence of Cusco Quechua on the Ecuadorean varieties in the Inca Empire. Because Northern nobles were required to educate their children in Cusco, this was maintained as the prestige dialect in the north.

Speakers from different points within any of the three regions can generally understand one another reasonably well. There are nonetheless significant local-level differences across each. (Wanka Quechua, in particular, has several very distinctive characteristics that make the variety more challenging to understand, even for other Central Quechua speakers.) Speakers from different major regions, particularly Central or Southern Quechua, are not able to communicate effectively.

The lack of mutual intelligibility among the dialects is the basic criterion that defines Quechua not as a single language, but as a language family. The complex and progressive nature of how speech varies across the dialect continua makes it nearly impossible to differentiate discrete varieties; Ethnologue lists 45 varieties which are then divided into two groups; Central and Peripheral. Due to the non-intelligibility between the two groups, they are all classified as separate languages.31

As a reference point, the overall degree of diversity across the family is a little less than that of the Romance or Germanic families, and more of the order of Slavic or Arabic. The greatest diversity is within Central Quechua, or Quechua I, which is believed to lie close to the homeland of the ancestral Proto-Quechua language.

Alfredo Torero devised the traditional classification, the three divisions above, plus a fourth, a northern or Peruvian branch. The latter causes complications in the classification, however, as various dialects (e.g. Cajamarca–Cañaris, Pacaraos, and Yauyos) have features of both Quechua I and Quechua II, and so are difficult to assign to either.

Torero classifies them as the following:

- Quechuan

- Quechua I or Quechua B, a.k.a. Central Quechua or Waywash, spoken in Peru’s central highlands and coast.

- The most widely spoken varieties are Huaylas, Huaylla Wanca, and Conchucos.

- Quechua II or Quechua A or Peripheral Quechua or Wanp’una, divided into

- Yungay (Yunkay) Quechua or Quechua II A, spoken in the northern mountains of Peru; the most widely spoken dialect is Cajamarca.

- Northern Quechua or Quechua II B, spoken in Ecuador (Kichwa), northern Peru, and Colombia (Inga Kichwa)

- The most widely spoken varieties in this group are Chimborazo Highland Quichua and Imbabura Highland Quichua.

- Southern Quechua or Quechua II C, spoken in Bolivia, Chile, southern Peru and Northwest Argentina.

- The most widely spoken varieties are South Bolivian, Cusco, Ayacucho, and Puno (Collao).

Willem Adelaar adheres to the Quechua I / Quechua II (central/peripheral) bifurcation. But, partially following later modifications by Torero, he reassigns part of Quechua II-A to Quechua I:32

Landerman (1991) does not believe a true genetic classification is possible and divides Quechua II so that the family has four geographical–typological branches: Northern, North Peruvian, Central, and Southern. He includes Chachapoyas and Lamas in North Peruvian Quechua so Ecuadorian is synonymous with Northern Quechua.33

Geographical distribution

Quechua I (Central Quechua, Waywash) is spoken in Peru’s central highlands, from the Ancash Region to Huancayo. It is the most diverse branch of Quechua,34 to the extent that its divisions are commonly considered different languages.

Quechua II (Peripheral Quechua, Wamp’una “Traveler”)

- II-A: Yunkay Quechua (North Peruvian Quechua) is scattered in Peru’s occidental highlands.

- II-B: Northern Quechua (also known as Runashimi or, especially in Ecuador, Kichwa) is mainly spoken in Colombia and Ecuador. It is also spoken in the Amazonian lowlands of Colombia and Ecuador, and in pockets of Peru.

- II-C: Southern Quechua, in the highlands further south, from Huancavelica through the Ayacucho, Cusco, and Puno regions of Peru, across much of Bolivia, and in pockets in north-western Argentina. It is the most influential branch, with the largest number of speakers and the most important cultural and literary legacy.

This is a sampling of words in several Quechuan languages:

| Ancash (I) | Wanka (I) | Cajamarca (II-A) | San Martin (II-B) | Kichwa (II-B) | Ayacucho (II-C) | Cusco (II-C) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘one’ | huk [uk ~ huk] | suk, huk [suk], [huk] | suq [soχ] | suk [suk] | shuk [ʃuk] | huk [huk] | huk [hoχ] |

| ‘two’ | ishkay [ɪʃkeˑ ~ ɪʃkɐj] | ishkay [iʃkaj] | ishkay [ɪʃkɐj] | ishkay [iʃkaj] | ishkay [iʃki ~ iʃkaj] | iskay [iskæj] | iskay [iskæj] |

| ‘ten’ | ćhunka, chunka [ʈ͡ʂʊŋkɐ], [t͡ʃʊŋkɐ] | ćhunka [ʈ͡ʂuŋka] | ch’unka [ʈ͡ʂʊŋɡɐ] | chunka [t͡ʃuŋɡa] | chunka [t͡ʃuŋɡɐ ~ t͡ʃuŋkɐ] | chunka [t͡ʃuŋkɐ] | chunka [t͡ʃuŋkɐ] |

| ‘sweet’ | mishki [mɪʃkɪ] | mishki [mɪʃkɪ] | mishki [mɪʃkɪ] | mishki [mɪʃkɪ] | mishki [mɪʃkɪ] | miski [mɪskɪ] | misk’i [mɪskʼɪ] |

| ‘white’ | yuraq [jʊɾɑq ~ jʊɾɑχ] | yulaq [julah ~ julaː] | yuraq [jʊɾɑx] | yurak [jʊɾak] | yurak [jʊɾax ~ jʊɾak] | yuraq [jʊɾɑχ] | yuraq [jʊɾɑχ] |

| ‘he gives’ | qun [qoŋ ~ χoŋ ~ ʁoŋ] | qun [huŋ ~ ʔuŋ] | qun [qoŋ] | kun [kuŋ] | kun [kuŋ] | qun [χoŋ] | qun [qoŋ] |

| ‘yes’ | awmi [oːmi ~ ɐwmɪ] | aw [aw] | ari [ɐɾi] | ari [aɾi] | ari [aɾi] | arí [ɐˈɾi] | arí [ɐˈɾi] |

Quechua shares a large amount of vocabulary, and some striking structural parallels, with Aymara, and the two families have sometimes been grouped together as a “Quechumaran family.” This hypothesis is generally rejected by specialists, however. The parallels are better explained by mutual influence and borrowing through intensive and long-term contact. Many Quechua–Aymara cognates are close, often closer than intra-Quechua cognates, and there is a little relationship in the affixal system. The Puquina language of the Tiwanaku Empire is a possible source for some of the shared vocabulary between Quechua and Aymara.27

Jolkesky (2016) notes that there are lexical similarities with the Kunza, Leko, Mapudungun, Mochika, Uru-Chipaya, Zaparo, Arawak, Kandoshi, Muniche, Pukina, Pano, Barbakoa, Cholon-Hibito, Jaqi, Jivaro, and Kawapana language families due to contact.35

![]()

Vocabulary of the general language of the Indians of Peru, called Quichua (1560). From Domingo de Santo Tomás, the first writer in Quechua.

Quechua has borrowed a large number of Spanish words, such as piru (from pero, “but”), bwenu (from bueno, “good”), iskwila (from escuela, “school”), waka (from vaca, “cow”) and wuru (from burro, “donkey”).36

A number of Quechua words have entered English and French via Spanish, including coca, condor, guano, jerky, llama, pampa, poncho, puma, quinine, quinoa, vicuña (vigogne in French), and, possibly, gaucho. The word lagniappe comes from the Quechuan word yapay “to increase, to add.” The word first came into Spanish then Louisiana French, with the French or Spanish article la in front of it, la ñapa in Louisiana French or Creole, or la yapa in Spanish. A rare instance of a Quechua word being taken into general Spanish use is given by carpa for “tent” (Quechua karpa).37

The Quechua influence on Latin American Spanish includes such borrowings as papa “potato”, chuchaqui “hangover” in Ecuador, and diverse borrowings for “altitude sickness”: suruqch’i in Bolivia, sorojchi in Ecuador, and soroche in Peru.

In Bolivia, particularly, Quechua words are used extensively even by non-Quechua speakers. These include wawa “baby, infant”, chʼaki “hangover”, misi “cat”, jukʼucho “mouse”, qʼumer uchu “green pepper”, jaku “let’s go”, chhiri and chhurco “curly haired”, among many others. Quechua grammar also enters Bolivian Spanish, such as the use of the suffix -ri. In Bolivian Quechua, -ri is added to verbs to signify an action is performed with affection or, in the imperative, as a rough equivalent to “please”. In Bolivia, -ri is often included in the Spanish imperative to imply “please” or to soften commands. For example, the standard pásame “pass me [something]” becomes pasarime.

Etymology of Quechua

At first, Spaniards referred to the language of the Inca empire as the lengua general, the general tongue. The name quichua was first used in 1560 by Domingo de Santo Tomás in his Grammatica o arte de la lengua general de los indios de los reynos del Perú.38 It is not known what name the native speakers gave to their language before colonial times and whether it was Spaniards who called it quechua.38

There are two possible etymologies of Quechua as the name of the language. There is a possibility that the name Quechua was derived from *qiĉwa, the native word which originally meant the “temperate valley” altitude ecological zone in the Andes (suitable for maize cultivation) and to its inhabitants.38 Alternatively, Pedro Cieza de León and Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, the early Spanish chroniclers, mention the existence of a people called Quichua in the present Apurímac Region, and it could be inferred that their name was given to the entire language.38

The Hispanicised spellings Quechua and Quichua have been used in Peru and Bolivia since the 17th century, especially after the Third Council of Lima. Today, the various local pronunciations of “Quechua” include [ˈqʰeʃwa ~ ˈqʰeswa], [ˈχɪt͡ʃwa], [ˈkit͡ʃwa], and [ˈʔiʈ͡ʂwa].

Another name that native speakers give to their own language is runa simi, “language of man/people”; it also seems to have emerged during the colonial period.38

The description below applies to Cuzco Quechua; there are significant differences in other varieties of Quechua.

Quechua only has three vowel phonemes: /a/ /i/ and /u/, with no diphthongs, as in Aymara (including Jaqaru). Monolingual speakers pronounce them as [æ, ɪ, ʊ] respectively, but Spanish realizations [ä, i, u] may also be found. When the vowels appear adjacent to uvular consonants (/q/, /qʼ/, and /qʰ/), they are rendered more like [ɑ, ɛ, ɔ], respectively.

Gemination of the tap /ɾ/ results in a trill [r].

Duration: 3 seconds.

Pronunciation of the voiceless bilabial plosives of Cusco Quechua

About 30% of the modern Quechua vocabulary is borrowed from Spanish, and some Spanish sounds (such as /f/, /b/, /d/, /ɡ/) may have become phonemic even among monolingual Quechua speakers.

Voicing is not phonemic in Cusco Quechua. Cusco Quechua, North Bolivian Quechua, and South Bolivian Quechua are the only varieties to have glottalized consonants. They, along with certain kinds of Ecuadorian Kichwa, are the only varieties which have aspirated consonants. Because reflexes of a given Proto-Quechua word may have different stops in neighboring dialects (Proto-Quechua *čaki ‘foot’ becomes č’aki and Proto-Quechua *čaka ‘bridge’ becomes čaka[non sequitur]), they are thought to be innovations in Quechua from Aymara, borrowed independently after branching off from Proto-Quechua.

Stress is penultimate in most dialects of Quechua. In some varieties, factors such as the apocope of word-final vowels may cause exceptional final stress. Stress in Chachapoyas Quechua falls word-initially.

Quechua has been written using the Roman alphabet since the Spanish conquest of Peru. However, written Quechua is rarely used by Quechua speakers due to limited amounts of printed material in the language.

Until the 20th century, Quechua was written with a Spanish-based orthography, for example Inca, Huayna Cápac, Collasuyo, Mama Ocllo, Viracocha, quipu, tambo, condor. This orthography is the most familiar to Spanish speakers, and so it has been used for most borrowings into English, which essentially always happen through Spanish.

In 1975, the Peruvian government of Juan Velasco Alvarado adopted a new orthography for Quechua. This is the system preferred by the Academia Mayor de la Lengua Quechua, which results in the following spellings of the examples listed above: Inka, Wayna Qhapaq, Qollasuyu, Mama Oqllo, Wiraqocha, khipu, tampu, kuntur. This orthography has the following features:

- It uses w instead of hu for /w/.

- It distinguishes velar k from uvular q, both of which were spelled c or qu in the traditional system.[example needed]

- It distinguishes simple, ejective, and aspirated stops in dialects that make these distinctions, such as that of the Cusco Region, e.g. the aspirated khipu ‘knot’.

- It continues to use the Spanish five-vowel system.

In 1985, a variation of this system was adopted by the Peruvian government that uses the Quechuan three-vowel system, resulting in the following spellings: Inka, Wayna Qhapaq, Qullasuyu, Mama Uqllu, Wiraqucha, khipu, tampu, kuntur.

The different orthographies are still highly controversial in Peru. Advocates of the traditional system believe that the new orthographies look too foreign and believe that it makes Quechua harder to learn for people who have first been exposed to written Spanish. Those who prefer the new system maintain that it better matches the phonology of Quechua, and they point to studies showing that teaching the five-vowel system to children later causes reading difficulties in Spanish.[citation needed]

For more on this, see Quechuan and Aymaran spelling shift.

Writers differ in the treatment of Spanish loanwords. These are sometimes adapted to modern orthography and sometimes left as in Spanish. For instance, “I am Roberto” could be written Robertom kani or Ruwirtum kani. (The -m is not part of the name; it is an evidential suffix, showing how the information is known: firsthand, in this case.)

The Peruvian linguist Rodolfo Cerrón Palomino has proposed an orthographic norm for all of Southern Quechua: this Standard Quechua (el Quechua estándar or Hanan Runasimi) conservatively integrates features of the two widespread dialects Ayacucho Quechua and Cusco Quechua. For instance:39

| English | Ayacucho | Cusco | Standard Quechua |

|---|---|---|---|

| to drink | upyay | uhyay | upyay |

| fast | utqa | usqha | utqha |

| to work | llamkay | llank’ay | llamk’ay |

| we (inclusive) | ñuqanchik | nuqanchis | ñuqanchik |

| (progressive suffix) | -chka- | -sha- | -chka- |

| day | punchaw | p’unchay | p’unchaw |

The Spanish-based orthography is now in conflict with Peruvian law. According to article 20 of the decree Decreto Supremo No 004-2016-MC, which approves regulations relative to Law 29735, published in the official newspaper El Peruano on July 22, 2016, adequate spellings of the toponyms in the normalized alphabets of the indigenous languages must progressively be proposed, with the aim of standardizing the spellings used by the National Geographic Institute (Instituto Geográfico Nacional, IGN) The IGN implements the necessary changes on the official maps of Peru.40

Quechua is an agglutinating language, meaning that words are built up from basic roots followed by several suffixes, each of which carries one meaning. Their large number of suffixes changes both the overall meaning of words and their subtle shades of meaning. All varieties of Quechua are very regular agglutinative languages, as opposed to isolating or fusional ones [Thompson]. Their normal sentence order is SOV (subject–object–verb). Notable grammatical features include bipersonal conjugation (verbs agree with both subject and object), evidentiality (indication of the source and veracity of knowledge), a set of topic particles, and suffixes indicating who benefits from an action and the speaker’s attitude toward it, but some varieties may lack some of the characteristics.

| Number | |||

| Singular | Plural | ||

| Person | First | Ñuqa | Ñuqanchik (inclusive) Ñuqayku (exclusive) |

| Second | Qam | Qamkuna | |

| Third | Pay | Paykuna | |

In Quechua, there are seven pronouns. First-person plural pronouns (equivalent to “we”) may be inclusive or exclusive; which mean, respectively, that the addressee (“you”) is or is not part of the “we”. Quechua also adds the suffix -kuna to the second and third person singular pronouns qam and pay to create the plural forms, qam-kuna and pay-kuna. In Quechua IIB, or “Kichwa”, the exclusive first-person plural pronoun, “ñuqayku”, is generally obsolete.

Adjectives in Quechua are always placed before nouns. They lack gender and number and are not declined to agree with nouns.

- Cardinal numbers. ch’usaq (0), huk (1), iskay (2), kimsa (3), tawa (4), pichqa (5), suqta (6), qanchis (7), pusaq (8), isqun (9), chunka (10), chunka hukniyuq (11), chunka iskayniyuq (12), iskay chunka (20), pachak (100), waranqa (1,000), hunu (1,000,000), lluna (1,000,000,000,000).

- Ordinal numbers. To form ordinal numbers, the word ñiqin is put after the appropriate cardinal number (iskay ñiqin = “second”). The only exception is that, in addition to huk ñiqin (“first”), the phrase ñawpaq is also used in the somewhat more restricted sense of “the initial, primordial, the oldest.”

Noun roots accept suffixes that indicate number, case, and the person of a possessor. In general, the possessive suffix precedes that of number. In the Santiago del Estero variety, however, the order is reversed.41 From variety to variety, suffixes may change.

| Function | Suffix | Example | (translation) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| suffix indicating number | plural | -kuna | wasikuna | houses |

| possessive suffix | 1.person singular | -y, -: | wasiy, wasii | my house |

| 2.person singular | -yki | wasiyki | your house | |

| 3.person singular | -n | wasin | his/her/its house | |

| 1.person plural (incl) | -nchik | wasinchik | our house (incl.) | |

| 1.person plural (excl) | -y-ku | wasiyku | our house (excl.) | |

| 2.person plural | -yki-chik | wasiykichik | your (pl.) house | |

| 3.person plural | -n-ku | wasinku | their house | |

| suffixes indicating case | nominative | – | wasi | the house (subj.) |

| accusative | -(k)ta | wasita | the house (obj.) | |

| instrumental | -wan | wasiwan | with the house, and the house | |

| abessive | -naq/-nax/-naa | wasinaq | without the house | |

| dative/benefactive | -paq/-pax/-paa | wasipaq | to/for the house | |

| genitive | -p(a) | wasip(a) | of the house | |

| causative | -rayku | wasirayku | because of the house | |

| locative | -pi | wasipi | at the house | |

| directional | -man | wasiman | towards the house | |

| inclusive | -piwan, puwan | wasipiwan, wasipuwan | including the house | |

| terminative | -kama, -yaq | wasikama, wasiyaq | up to the house | |

| transitive | -(ni)nta | wasinta | through the house | |

| ablative | -manta, -piqta, -pu | wasimanta, wasipiqta | off/from the house | |

| comitative | -(ni)ntin | wasintin | along with the house | |

| immediate | -raq/-rax/-raa | wasiraq | first the house | |

| intrative | -pura | wasipura | among the houses | |

| exclusive | -lla(m) | wasilla(m) | only the house | |

| comparative | -naw, -hina | wasinaw, wasihina | than the house | |

Adverbs can be formed by adding -ta or, in some cases, -lla to an adjective: allin – allinta (“good – well”), utqay – utqaylla (“quick – quickly”). They are also formed by adding suffixes to demonstratives: chay (“that”) – chaypi (“there”), kay (“this”) – kayman (“hither”).

There are several original adverbs. For Europeans, it is striking that the adverb qhipa means both “behind” and “future” and ñawpa means “ahead, in front” and “past.”42 Local and temporal concepts of adverbs in Quechua (as well as in Aymara) are associated to each other reversely, compared to European languages. For the speakers of Quechua, we are moving backwards into the future (we cannot see it: it is unknown), facing the past (we can see it: it is remembered).

The infinitive forms have the suffix -y (e.g.., much’a ‘kiss’; much’a-y ‘to kiss’). These are the typical endings for the indicative in a Southern Quechua (IIC) dialect:

| Present | Past | Past habitual | Future | Pluperfect | Optative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ñuqa | -ni | -rqa-ni | -qka-ni | -saq | -sqa-ni | -yman |

| qam | -nki | -rqa-nki | -qka-nki | -nki | -sqa-nki | -nki-man -waq |

| pay | -n | -rqa(-n) | -q | -nqa | -sqa | -nman |

| ñuqanchik | -nchik | -rqa-nchik | -qka-nchik | -su-nchik | -sqa-nchik | -nchik-man -sun(-chik)-man -swan |

| ñuqayku | -yku | -rqa-yku | -qka-yku | -saq-ku | -sqa-yku | -yku-man |

| qamkuna | -nki-chik | -rqa-nki-chik | -qka-nki-chik | -nki-chik | -sqa-nki-chik | -nki-chik-man -waq-chik |

| paykuna | -n-ku | -rqa-(n)ku | -q-ku | -nqa-ku | -sqa-ku | -nku-man |

The suffixes shown in the table above usually indicate the subject; the person of the object is also indicated by a suffix, which precedes the suffixes in the table. For the second person, it is -su-, and for the first person, it is -wa- in most Quechua II dialects. In such cases, the plural suffixes from the table (-chik and -ku) can be used to express the number of the object rather than the subject. There is a lot of variation between the dialects in the exact rules which determine this.434445 In Central Quechua, however, the verbal morphology differs in a number of respects: most notably, the verbal plural suffixes -chik and -ku are not used, and plurality is expressed by different suffixes that are located before rather than after the personal suffixes. Furthermore, the 1st person singular object suffix is -ma-, rather than -wa-.46

Grammatical particles

Particles are indeclinable: they do not accept suffixes. They are relatively rare, but the most common are arí ‘yes’ and mana ‘no’, although mana can take some suffixes, such as -n/-m (manan/manam), -raq (manaraq ‘not yet’) and -chu (manachu? ‘or not?’), to intensify the meaning. Other particles are yaw ‘hey, hi’, and certain loan words from Spanish, such as piru (from Spanish pero ‘but’) and sinuqa (from sino ‘rather’).

The Quechuan languages have three different morphemes that mark evidentiality. Evidentiality refers to a morpheme whose primary purpose is to indicate the source of information.47 In Quechuan languages, evidentiality is a three-term system: there are three evidential morphemes that mark varying levels of source information. The markers can apply to first, second, and third persons.48 The chart below depicts an example of these morphemes from Wanka Quechua:49

| -m(i) | -chr(a) | -sh(i) |

|---|---|---|

| Direct evidence | Inferred; conjecture | Reported; hearsay |

DIR:direct evidence CONJ:conjecture

The parentheses around the vowels indicate that the vowel can be dropped when following an open vowel. For the sake of cohesiveness, the above forms are used to discuss the evidential morphemes. There are dialectal variations to the forms. The variations will be presented in the following descriptions.

The following sentences provide examples of the three evidentials and further discuss the meaning behind each of them.

-m(i) : Direct evidence and commitment

50 Regional variations: In Cusco Quechua, the direct evidential presents itself as –mi and –n.

The evidential –mi indicates that the speaker has a “strong personal conviction the veracity of the circumstance expressed.”51 It has the basis of direct personal experience.

Wanka Quechua52

ñawi-i-wan-mi

eye-1P-with-DIR

ñawi-i-wan-mi lika-la-a

eye-1P-with-DIR see-PST-1

I saw them with my own eyes.

-chr(a) : Inference and attenuation

In Quechuan languages, not specified by the source, the inference morpheme appears as -ch(i), -ch(a), -chr(a).

The -chr(a) evidential indicates that the utterance is an inference or form of conjecture. That inference relays the speaker’s non-commitment to the truth-value of the statement. It also appears in cases such as acquiescence, irony, interrogative constructions, and first person inferences. These uses constitute nonprototypical use and will be discussed later in the changes in meaning and other uses section.

Wanka Quechua54

kuti-mu-n’a-qa-chr

return-AFAR-3FUT-now-CONJ

kuti-mu-n’a-qa-chr ni-ya-ami

return-AFAR-3FUT-now-CONJ say-IMPV-1-DIR

I think they will probably come back. Unknown glossing abbreviation(s) (help);

55 Regional variations: It can appear as –sh(i) or –s(i) depending on the dialect.

With the use of this morpheme, the speaker “serves as a conduit through which information from another source passes.” The information being related is hearsay or revelatory in nature. It also works to express the uncertainty of the speaker regarding the situation. However, it also appears in other constructions that are discussed in the changes in meaning section.

Wanka Quechua56

prista-ka-mu-la

borrow-REF-AFAR-PST

shanti-sh prista-ka-mu-la

Shanti-HSY borrow-REF-AFAR-PST

(I was told) Shanti borrowed it. Unknown glossing abbreviation(s) (help);

Hintz discusses an interesting case of evidential behavior found in the Sihaus dialect of Ancash Quechua. The author postulates that instead of three single evidential markers, that Quechuan language contains three pairs of evidential markers.57

The evidential morphemes have been referred to as markers or morphemes. The literature seems to differ on whether or not the evidential morphemes are acting as affixes or clitics, in some cases, such as Wanka Quechua, enclitics. Lefebvre and Muysken (1998) discuss this issue in terms of case but remark the line between affix and clitic is not clear.58 Both terms are used interchangeably throughout these sections.

Position in the sentence

Evidentials in the Quechuan languages are “second position enclitics”, which usually attach to the first constituent in the sentence, as shown in this example.59

machucha-piwan

old.man-WITH

huk-si ka-sqa huk machucha-piwan payacha

once-HSY be-SD one old.man-WITH woman

Once, there were an old man and an old woman. Unknown glossing abbreviation(s) (help);

They can, however, also occur on a focused constituent.

Pidru kunana-mi wasi-ta tuwa-sha-n

Pedro now-DIR.EV house-ACC build-PROG-3SG

It is now that Pedro is building the house.

Sometimes, the affix is described as attaching to the focus, particularly in the Tarma dialect of Yaru Quechua,60 but this does not hold true for all varieties of Quechua. In Huanuco Quechua, the evidentials may follow any number of topics, marked by the topic marker –qa, and the element with the evidential must precede the main verb or be the main verb.

However, there are exceptions to that rule, and the more topics there are in a sentence, the more likely the sentence is to deviate from the usual pattern.

Chawrana-qa

so:already-TOP

puntataruu-qu

at:the:peak-TOP

trayaruptin-qa

arriving-TOP

heqarkaykachisha

had:taken:her:up

syelutana-shi

to:heaven:already-IND

Chawrana-qa puntataruu-qu trayaruptin-qa wamrata-qa mayna-shi Diosninchi-qa heqarkaykachisha syelutana-shi

so:already-TOP at:the:peak-TOP arriving-TOP child-TOP already-IND our:God-TOP had:taken:her:up to:heaven:already-IND

When she (the witch) reached the peak, God had already taken the child up into heaven.

Changes in meaning and other uses

Evidentials can be used to relay different meanings depending on the context and perform other functions. The following examples are restricted to Wanka Quechua.

The direct evidential, -mi

The direct evidential appears in wh-questions and yes/no questions. By considering the direct evidential in terms of prototypical semantics, it seems somewhat counterintuitive to have a direct evidential, basically an evidential that confirms the speaker’s certainty about a topic, in a question. However, if one focuses less on the structure and more on the situation, some sense can be made. The speaker is asking the addressee for information so the speaker assumes the speaker knows the answer. That assumption is where the direct evidential comes into play. The speaker holds a certain amount of certainty that the addressee will know the answer. The speaker interprets the addressee as being in “direct relation” to the proposed content; the situation is the same as when, in regular sentences, the speaker assumes direct relation to the proposed information.61

kuti-mu-la

return-AFAR-PAST

imay-mi wankayuu-pu kuti-mu-la

when-DIR Huancayo-ABL return-AFAR-PAST

When did he come back from Huancayo?

(Floyd 1999, p. 85) Unknown glossing abbreviation(s) (help);

The direct evidential affix is also seen in yes/no questions, similar to the situation with wh-questions. Floyd describes yes/no questions as being “characterized as instructions to the addressee to assert one of the propositions of a disjunction.”62 Once again, the burden of direct evidence is being placed on the addressee, not on the speaker. The question marker in Wanka Quechua, -chun, is derived from the negative –chu marker and the direct evidential (realized as –n in some dialects).

tarma-kta li-n-chun

Tarma-ACC go-3-YN

Is he going to Tarma?

(Floyd 1999, p. 89) Unknown glossing abbreviation(s) (help);

Inferential evidential, -chr(a)

While –chr(a) is usually used in an inferential context, it has some non-prototypical uses.

Mild Exhortation In these constructions the evidential works to reaffirm and encourage the addressee’s actions or thoughts.

ni-nki-chra-ri

say-2-CONJ-EMPH

mas kalu-kuna-kta li-la-a ni-nki-chra-ri

more far-PL-ACC go-PST-1 say-2-CONJ-EMPH

Yes, tell them, “I’ve gone farther.”

(Floyd 1999, p. 107)

This example comes from a conversation between husband and wife, discussing the reactions of their family and friends after they have been gone for a while. The husband says he plans to stretch the truth and tell them about distant places to which he has gone, and his wife (in the example above) echoes and encourages his thoughts.

Acquiescence With these, the evidential is used to highlight the speaker’s assessment of inevitability of an event and acceptance of it. There is a sense of resistance, diminished enthusiasm, and disinclination in these constructions.

paaga-lla-shrayki-chra-a

pay-POL-1›2FUT-CONJ-EMPH

paaga-lla-shrayki-chra-a

pay-POL-1›2FUT-CONJ-EMPH

I suppose I’ll pay you then.

(Floyd 1999, p. 109) Unknown glossing abbreviation(s) (help);

This example comes from a discourse where a woman demands compensation from the man (the speaker in the example) whose pigs ruined her potatoes. He denies the pigs as being his but finally realizes he may be responsible and produces the above example.

Interrogative Somewhat similar to the –mi evidential, the inferential evidential can be found in content questions. However, the salient difference between the uses of the evidentials in questions is that in the –m(i) marked questions, an answer is expected. That is not the case with –chr(a) marked questions.

ima-lla-kta-chr

what-LIM-ACC-CONJ

u-you-shrun

give-ASP-12FUT

ayllu-kuna-kta-si

family-PL-ACC-EVEN

ima-lla-kta-chr u-you-shrun llapa ayllu-kuna-kta-si chra-alu-l

what-LIM-ACC-CONJ give-ASP-12FUT all family-PL-ACC-EVEN arrive-ASP-SS

I wonder what we will give our families when we arrive.

(Floyd 1999, p. 111) Unknown glossing abbreviation(s) (help);

Irony Irony in language can be a somewhat complicated topic in how it functions differently in languages, and by its semantic nature, it is already somewhat vague. For these purposes, it is suffice to say that when irony takes place in Wanka Quechua, the –chr(a) marker is used.

chay-nuu-pa-chr

that-SIM-GEN-CONJ

chay-nuu-pa-chr yachra-nki

that-SIM-GEN-CONJ know-2

(I suppose) That’s how you learn [that is the way in which you will learn].

(Floyd 199, p. 115) Unknown glossing abbreviation(s) (help);

This example comes from discourse between a father and daughter about her refusal to attend school. It can be interpreted as a genuine statement (perhaps one can learn by resisting school) or as an ironic statement (that is an absurd idea).

Hearsay evidential, -sh(i)

Aside from being used to express hearsay and revelation, this affix also has other uses.

Folktales, myths, and legends

Because folktales, myths, and legends are, in essence, reported speech, it follows that the hearsay marker would be used with them. Many of these types of stories are passed down through generations, furthering this aspect of reported speech. A difference between simple hearsay and folktales can be seen in the frequency of the –sh(i) marker. In normal conversation using reported speech, the marker is used less, to avoid redundancy.

Riddles

Riddles are somewhat similar to myths and folktales in that their nature is to be passed by word of mouth.

ayka-lla-sh

how

ima-lla-shi ayka-lla-sh juk machray-chru puñu-ya-n puka waaka

what-LIM-HSY how^much-LIM-HSY one cave-LOC sleep-IMPF-3 red cow

(Floyd 1999, p. 142) Unknown glossing abbreviation(s) (help);

Omission and overuse of evidential affixes

In certain grammatical structures, the evidential marker does not appear at all. In all Quechuan languages the evidential will not appear in a dependent clause. No example was given to depict this omission.63 Omissions occur in Quechua. The sentence is understood to have the same evidentiality as the other sentences in the context. Quechuan speakers vary as to how much they omit evidentials, but they occur only in connected speech.64

An interesting contrast to omission of evidentials is overuse of evidentials. If a speaker uses evidentials too much with no reason, competence is brought into question. For example, the overuse of –m(i) could lead others to believe that the speaker is not a native speaker or, in some extreme cases, that one is mentally ill.48

By using evidentials, the Quechua culture has certain assumptions about the information being relayed. Those who do not abide by the cultural customs should not be trusted. A passage from Weber (1986) summarizes them nicely below:

- (Only) one’s experience is reliable.

- Avoid unnecessary risk by assuming responsibility for information of which one is not absolutely certain.

- Do not be gullible. There are many folktales in which the villain is foiled by his gullibility.

- Assume responsibility only if it is safe to do so. Successful assumption of responsibility builds stature in the community.65

Evidentials also show that being precise and stating the source of one’s information is extremely important in the language and the culture. Failure to use them correctly can lead to diminished standing in the community. Speakers are aware of the evidentials and even use proverbs to teach children the importance of being precise and truthful. Precision and information source are of the utmost importance. They are a powerful and resourceful method of human communication.66

Act of Argentine Independence, written in Spanish and Quechua (1816)

As in the case of the pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, there are a number of Andean texts in the local language which were written down in Latin characters after the European conquest, but which express, to a great extent, the culture of pre-Conquest times. For example, Quechua poems thought to date from Inca times are preserved as quotations within some Spanish-language chronicles dealing with the pre-Conquest period. However, the most important specimen of Quechua literature of this type is the so-called Huarochirí Manuscript (1598), which describes the mythology and religion of the valley of Huarochirí and has been compared to “an Andean Bible” and to the Mayan Popol Vuh. From the post-conquest period (starting from the middle of the 17th century), there are a number of anonymous or signed Quechua dramas, some of which deal with the Inca era, while most are on religious topics and of European inspiration. The most famous dramas are Ollantay and the plays describing the death of Atahualpa. Juan de Espinosa Medrano wrote several dramas in the language. Poems in Quechua were also composed during the colonial period. A notable example are the works of Juan Wallparrimachi, a participant in the Bolivian War of Independence.6768

As for Christian literature, as early as 1583, the Third Provincial Church Council of Lima, which took place in 1583, published a number of texts dealing with Christian doctrine and rituals, including a trilingual catechism in Spanish, Quechua and Aymara69 and a number of other similar texts in the years from 1584 to 1585. More texts of this type were published until the middle of the 17th century, mostly adhering to a Quechua literary standard that had been codified by the Third Council for this purpose.70 There is at least one Quechuan version of the Bible.22

Dramas and poems continued to be written in the 19th and especially in 20th centuries as well; in addition, in the 20th century and more recently, more prose has been published. However, few literary forms were made present in the 19th century as European influences limited literary criticism.71 While some of that literature consists of original compositions (poems and dramas), the bulk of 20th century Quechua literature consists of traditional folk stories and oral narratives.67 Johnny Payne has translated two sets of Quechua oral short stories, one into Spanish and the other into English.

Demetrio Túpac Yupanqui wrote a Quechuan version of Don Quixote,22 under the title Yachay sapa wiraqucha dun Qvixote Manchamantan.72

A news broadcast in Quechua, “Ñuqanchik” (all of us), began in Peru in 2016.73

Many Andean musicians write and sing in their native languages, including Quechua and Aymara. Notable musical groups are Los Kjarkas, Kala Marka, J’acha Mallku, Savia Andina, Wayna Picchu, Wara, Alborada, Uchpa, and many others.

There are several Quechua and Quechua-Spanish bloggers, as well as a Quechua language podcast.74

The 1961 Peruvian film Kukuli was the first film to be spoken in the Quechua language.75

In the 1977 science fiction film Star Wars, the alien character Greedo speaks a simplified form of Quechua.76

The first-person shooter game Overwatch 2 features a Peruvian character, Illari, with some voice lines being in Quechua.

- Languages of Peru

- Andes

- Quechua People

- Aymara language

- List of English words of Quechuan origin

- Quechuan and Aymaran spelling shift

- South Bolivian Quechua

- Sumak Kawsay

- International Mother Language Day

- Intercultural bilingual education

- List of English words from Indigenous languages of the Americas

- Indigenous languages of the Americas

-

Rolph, Karen Sue. Ecologically Meaningful Toponyms: Linking a lexical domain to production ecology in the Peruvian Andes. Doctoral Dissertation, Stanford University, 2007.

-

Adelaar, Willem F. H (2004-06-10). The Languages of the Andes. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139451123. Archived from the original on 2024-05-26. Retrieved 2016-01-05.

-

Adelaar, Willem. The Languages of the Andes. With the collaboration of P.C. Muysken. Cambridge language survey. Cambridge University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-521-36831-5

-

Cerrón-Palomino, Rodolfo. Lingüística Quechua, Centro de Estudios Rurales Andinos ‘Bartolomé de las Casas’, 2nd ed. 2003

-

Cole, Peter. “Imbabura Quechua”, North-Holland (Lingua Descriptive Studies 5), Amsterdam 1982.

-

Cusihuamán, Antonio, Diccionario Quechua Cuzco-Collao, Centro de Estudios Regionales Andinos “Bartolomé de Las Casas”, 2001, ISBN 9972-691-36-5

-

Cusihuamán, Antonio, Gramática Quechua Cuzco-Collao, Centro de Estudios Regionales Andinos “Bartolomé de Las Casas”, 2001, ISBN 9972-691-37-3

-

Mannheim, Bruce, The Language of the Inka since the European Invasion, University of Texas Press, 1991, ISBN 0-292-74663-6

-

Rodríguez Champi, Albino. (2006). Quechua de Cusco. Ilustraciones fonéticas de lenguas amerindias, ed. Stephen A. Marlett. Lima: SIL International y Universidad Ricardo Palma. Lengamer.org Archived 2018-12-21 at the Wayback Machine

-

Aikhenvald, Alexandra. Evidentiality. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2004. Print.

-

Floyd, Rick. The Structure of Evidential Categories in Wanka Quechua. Dallas, TX: Summer Institute of Linguistics, 1999. Print.

-

Hintz, Diane. “The evidential system in Sihuas Quechua: personal vs. shared knowledge” The Nature of Evidentiality Conference, The Netherlands, 14–16 June 2012. SIL International. Internet. 13 April 2014.

-

Lefebvre, Claire, and Pieter Muysken. Mixed Categories: Nominalizations in Quechua. Dordrecht, Holland: Kluwer Academic, 1988. Print.

-

Weber, David. “Information Perspective, Profile, and Patterns in Quechua.” Evidentiality: The Linguistic Coding of Epistemology. Ed. Wallace L. Chafe and Johanna Nichols. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Pub, 1986. 137–55. Print.

-

Adelaar, Willem F. H. Modeling convergence: Towards a reconstruction of the history of Quechuan–Aymaran interaction About the origin of Quechua, and its relation with Aymara, 2011.

-

Adelaar, Willem F. H. Tarma Quechua: Grammar, Texts, Dictionary. Lisse: Peter de Ridder Press, 1977.

-

Bills, Garland D., Bernardo Vallejo C., and Rudolph C. Troike. An Introduction to Spoken Bolivian Quechua. Special publication of the Institute of Latin American Studies, the University of Texas at Austin. Austin: Published for the Institute of Latin American Studies by the University of Texas Press, 1969. ISBN 0-292-70019-9

-

Coronel-Molina, Serafín M. Quechua Phrasebook. 2002 Lonely Planet ISBN 1-86450-381-5

-

Curl, John, Ancient American Poets. Tempe AZ: Bilingual Press, 2005.ISBN 1-931010-21-8 Red-coral.net Archived 2020-11-12 at the Wayback Machine

-

Gifford, Douglas. Time Metaphors in Aymara and Quechua. St. Andrews: University of St. Andrews, 1986.

-

Heggarty and David Beresford-Jones, Paul (2012), Archaeology and Language in the Andes, Oxford: Oxford University Press

-

Harrison, Regina. Signs, Songs, and Memory in the Andes: Translating Quechua Language and Culture. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1989. ISBN 0-292-77627-6

-

Jake, Janice L. Grammatical Relations in Imbabura Quechua. Outstanding dissertations in linguistics. New York: Garland Pub, 1985. ISBN 0-8240-5475-X

-

King, Kendall A. Language Revitalization Processes and Prospects: Quichua in the Ecuadorian Andes. Bilingual education and bilingualism, 24. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters LTD, 2001. ISBN 1-85359-495-4

-

King, Kendall A., and Nancy H. Hornberger. Quechua Sociolinguistics. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2004.

-

Lara, Jesús, Maria A. Proser, and James Scully. Quechua Peoples Poetry. Willimantic, Conn: Curbstone Press, 1976. ISBN 0-915306-09-3

-

Lefebvre, Claire, and Pieter Muysken. Mixed Categories: Nominalizations in Quechua. Studies in natural language and linguistic theory, [v. 11]. Dordrecht, Holland: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1988. ISBN 1-55608-050-6

-

Lefebvre, Claire, and Pieter Muysken. Relative Clauses in Cuzco Quechua: Interactions between Core and Periphery. Bloomington, Ind: Indiana University Linguistics Club, 1982.

-

Muysken, Pieter. Syntactic Developments in the Verb Phrase of Ecuadorian Quechua. Lisse: Peter de Ridder Press, 1977. ISBN 90-316-0151-9

-

Nuckolls, Janis B. Sounds Like Life: Sound-Symbolic Grammar, Performance, and Cognition in Pastaza Quechua. Oxford studies in anthropological linguistics, 2. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996. ISBN

-

Parker, Gary John. Ayacucho Quechua Grammar and Dictionary. Janua linguarum. Series practica, 82. The Hague: Mouton, 1969.

-

Plaza Martínez, Pedro. Quechua. In: Mily Crevels and Pieter Muysken (eds.) Lenguas de Bolivia, vol. I, 215–284. La Paz: Plural editores, 2009. ISBN 978-99954-1-236-4. (in Spanish)

-

Sánchez, Liliana. Quechua-Spanish Bilingualism: Interference and Convergence in Functional Categories. Language acquisition & language disorders, v. 35. Amsterdam: J. Benjamins Pub, 2003. ISBN 1-58811-471-6

-

Weber, David. A Grammar of Huallaga (Huánuco) Quechua. University of California publications in linguistics, v. 112. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989. ISBN 0-520-09732-7

-

Quechua bibliographies online at: quechua.org.uk Archived 2020-09-25 at the Wayback Machine

Dictionaries and lexicons

- Parker, G. J. (1969). Ayacucho Quechua grammar and dictionary. (Janua linguarum: Series practica, 82). The Hague: Mouton.

- Cachique Amasifuén, S. F. (2007). Diccionario Kichwa-Castellano / Castellano- Kichwa. Tarapoto, San Martín: Aquinos.

- Cerrón-Palomino, R. (1994). Quechua sureño, diccionario unificado quechua- castellano, castellano-quechua. Lima: Biblioteca Nacional del Perú.

- Cusihuamán G., A. (1976). Diccionario quechua: Cuzco-Collao. Lima: Ministerio de Educación.

- Shimelman, A. (2012–2014). Southern Yauyos Quechua Lexicon. Lima: PUCP.

- Stark, L. R.; Muysken, P. C. (1977). Diccionario español-quichua, quichua español. (Publicaciones de los Museos del Banco Central del Ecuador, 1). Quito: Guayaquil.

- Tödter, Ch.; Zahn, Ch.; Waters, W.; Wise, M. R. (2002). Shimikunata asirtachik killka inka-kastellanu (Diccionario inga-castellano) (Serie lingüística Peruana, 52). Lima: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

- Weber, D. J.; Ballena D., M.; Cayco Z., F.; Cayco V., T. (1998). Quechua de Huánuco: Diccionario del quechua del Huallaga con índices castellano e ingles (Serie Lingüística Peruana, 48). Lima: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

- Weber, N. L.; Park, M.; Cenepo S., V. (1976). Diccionario quechua: San Martín. Lima: Ministerio de Educación.

Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Quechua

- Quechua lessons at www.andes.org (in Spanish and English)

- Detailed map of the varieties of Quechua according to SIL (fedepi.org)

- Quechua Collection of Patricia Dreidemie at the Archive of the Indigenous Languages of Latin America.

- Huancavelica Quechua Fieldnotes of Willem de Ruese, copies of handwritten notes on Quechua pedagogical and descriptive materials, from the Archive of the Indigenous Languages of Latin America.

- Diccionario Quechua: Español–Runasimi–English—Dictionary of Ayacucho Quechua from Clodoaldo Soto Ruiz.

- information about Quechua in a variety of languages

- Quechua dramatic and lyrical works (Dramatische und lyrische Dichtungen der Keshua-Sprache) by Ernst Middendorf (bilingual Quechua – German edition, 1891)

- Ollantay (Ollanta: ein drama der Keshuasprache), ed. by Ernst Middendorf (bilingual Quechua – German edition, 1890)

Footnotes

-

“Longman Dictionary”. Archived from the original on 2024-05-26. Retrieved 2018-06-02. ↩

-

Oxford Living Dictionaries, British and World English ↩

-

Cerrón-Palomino, Rodolfo (2003). Lingüística quechua. Monumenta lingüística andina (2. ed.). Cuzco: Centro de Estudios Regionales Andinos Bartolomé de Las Casas. ISBN 978-9972-691-59-1. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Adelaar, Willem F. H.; Muysken, Pieter (2004). The languages of the Andes. Cambridge language surveys. Cambridge (G.B.): Cambridge University press. ISBN 978-0-521-36275-7. ↩ ↩2

-

Torero, Alfredo (2002). Idiomas de los Andes: linguistica e historia. Travaux de l’Institut Français d’études andines. Lima: Instituto Francés de estudios andinos Editorial horizonte. ISBN 978-9972-699-27-6. ↩ ↩2

-

Heggarty, Paul; Beresford-Jones, David, eds. (2012-05-17). Archaeology and Language in the Andes (1 ed.). British Academy. doi:10.5871/bacad/9780197265031.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-726503-1. ↩ ↩2

-

Howard, Rosaleen (2011), Heggarty, Paul; Pearce, Adrian J. (eds.), “The Quechua Language in the Andes Today: Between Statistics, the State, and Daily Life”, History and Language in the Andes, Studies of the Americas, New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, pp. 189–213, doi:10.1057/9780230370579_9, ISBN 978-0-230-37057-9, archived from the original on 2024-05-26, retrieved 2024-01-09 ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

“Perú Resultados Definitivos de los Censos Nacionales”. Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. 2017. Archived from the original on Apr 6, 2023. Retrieved 12 December 2023. ↩

-

Heggarty, Paul (October 2007). “Linguistics for Archaeologists: Principles, Methods and the Case of the Incas”. Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 17 (3): 311–340. doi:10.1017/S095977430700039X. ISSN 0959-7743. S2CID 59132956. Archived from the original on 2024-05-26. Retrieved 2024-01-09. ↩

-

Adelaar, Willem F. H.. Chapter Languages of the Middle Andes in Areal-typological Perspective. Germany, De Gruyter, 2012. ↩

-

Fisher, John; Cahill, David Patrick, eds. (2008). De la etnohistoria a la historia en los Andes : 51o Congreso Internacional de Americanistas, Santiago de Chile, 2003. Congreso Internacional de Americanistas. p. 295. ISBN 9789978227398. Archived from the original on 2024-05-26. Retrieved 2020-11-07. ↩

-

Torero, Alfredo (1983). “La familia lingûística quechua”. América Latina en sus lenguas indígenas. Caracas: Monte Ávila. ISBN 92-3-301926-8. ↩

-

Torero, Alfredo (1974). El quechua y la historia social andina. Lima: Universidad Ricardo Palma, Dirección Universitaria de Investigación. ISBN 978-603-45-0210-9. ↩

-

Aybar cited by Hart, Stephen M. A Companion to Latin American Literature, p. 6. ↩

-

Hernández, Arturo (1 January 1981). “Influencia del mapuche en el castellano”. Revista Documentos Lingüísticos y Literarios UACh (7). Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 7 November 2020. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Téllez, Eduardo (2008). Los Diaguitas: Estudios (in Spanish). Santiago, Chile: Ediciones Akhilleus. p. 43. ISBN 978-956-8762-00-1. ↩

-

Ramírez Sánchez, Carlos (1995). Onomástica indígena de Chile: Toponimia de Osorno, Llanquihue y Chiloé (in Spanish) (2nd ed.). Valdivia: Universidad Austral de Chile. ↩

-

Payàs Puigarnau, Getrudis; Villena Araya, Belén (2021-12-15). “Indagaciones en torno al significado del oro en la cultura mapuche. Una exploración de fuentes y algo más” [Inquiries on the Meaning of Gold in Mapuche Culture. A review of sources and something more]. Estudios Atacameños (in Spanish). 67. doi:10.22199/issn.0718-1043-2021-0028. S2CID 244279716. Archived from the original on 2023-03-26. Retrieved 2023-04-25. ↩

-

Ramírez Sanchez, Carlos (1988). Toponimia indígena de las provincias de Osorno, Llanquihue y Chiloé (in Spanish). Valdivia: Marisa Cuneo Ediciones. p. 28. ↩

-

Londoño, Vanessa (October 5, 2016). “Why a Quechua Novelist Doesn’t Want His Work Translated”. Americas Quarterly. Archived from the original on Oct 31, 2023. ↩

-

Collyns, Dan (2019-10-27). “Student in Peru makes history by writing thesis in the Incas’ language”. The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2024-05-26. Retrieved 2019-10-28. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

""El problema es que no puedas acceder a tus derechos solo por ser hablante de una lengua originaria"". ↩

-

Kandell, Jonathan Gay (May 22, 1975). “Peru officially adopting Indian tongue”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 27, 2020. Retrieved April 22, 2016. ↩

-

Borsdorf, Axel (12 March 2015). The Andes: A Geographical Portrait. Springer. p. 142. ISBN 9783319035307. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 7 November 2020. ↩

-

Adelaar 2004, pp. 258–259: “The Quechua speakers’ wish for social mobility for their children is often heard as an argument for not transmitting the language to the next generation… As observed quite adequately by Cerrón Palomino, “Quechua (and Aymara) speakers seem to have taken the project of assimilation begun by the dominating classes and made it their own.” ↩

-

Moulian, Rodrigo; Catrileo, María; Landeo, Pablo (December 2015). “Afines Quechua en el Vocabulario Mapuche de Luis de Valdivia”. RLA. Revista de lingüística teórica y aplicada. 53 (2): 73–96. doi:10.4067/S0718-48832015000200004. ↩ ↩2

-

“Alain Fabre, Diccionario etnolingüístico y guía bibliográfica de los pubelos indígenas sudamericanos”. Archived from the original on 2020-09-25. Retrieved 2016-09-23. ↩

-

“Inei – Redatam Censos 2017”. Archived from the original on 2018-09-13. Retrieved 2018-09-17. ↩

-

Claudio Torrens (2011-05-28). “Some NY immigrants cite lack of Spanish as barrier”. San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on 2015-02-01. Retrieved 2022-08-20. ↩

-

Adelaar 2004.[page needed] ↩

-

Peter Landerman, 1991. Quechua dialects and their classification. PhD dissertation, UCLA ↩

-

Lyle Campbell, American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America, Oxford University Press, 1997, p. 189 ↩

-

Jolkesky, Marcelo Pinho de Valhery (2016). Estudo arqueo-ecolinguístico das terras tropicais sul-americanas (Ph.D. dissertation) (2 ed.). Brasília: University of Brasília. Archived from the original on 2021-04-18. Retrieved 2020-06-04. ↩

-

Muysken, Pieter (March 2012). “Root/affix asymmetries in contact and transfer: case studies from the Andes”. International Journal of Bilingualism. 16 (1): 22–36. doi:10.1177/1367006911403211. S2CID 143633302. ↩

-

Edward A. Roberts, A Comprehensive Etymological Dictionary of the Spanish Language…, 2014. ↩

-

To listen to recordings of these and many other words as pronounced in many different Quechua-speaking regions, see the external website The Sounds of the Andean Languages Archived 2007-01-09 at the Wayback Machine. It also has an entire section on the new Quechua and Aymara Spelling Archived 2013-11-11 at the Wayback Machine. ↩

-

“Decreto Supremo que aprueba el Reglamento de la Ley N° 29735, Ley que regula el uso, preservación, desarrollo, recuperación, fomento y difusión de las lenguas originarias del Perú, Decreto Supremo N° 004-2016-MC”. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved July 10, 2017. ↩

-

Alderetes, Jorge R. (1997). “Morfología nominal del quechua santiagueño”. Archived from the original on 2017-10-11. Retrieved 2008-01-21. ↩

-

This occurs in English, where “before” means “in the past”, and Shakespeare’s Macbeth says “The greatest is behind”, meaning in the future. ↩

-

Wunderlich, Dieter (2005). Variation der Person-Numerus-Flexion in Quechua Archived 2024-05-26 at the Wayback Machine. Flexionsworkshop Leipzig, 14. Juli 2005] ↩

-

Lakämper, Renate, Dieter Wunderlich. 1998. Person marking in Quechua: a constraint-based minimalist analysis. Lingua 105: pp. 113–48. ↩

-

“Lakämper, Renate. 2000. Plural- und Objektmarkierung in Quechua. Doctoral Dissertation. Philosophische Fakultät der Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf”. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. ↩

-

Adelaar 2007: 189 ↩

-

Aikhenvald 2004, p. 3. ↩

-

Aikhenvald 2004, p. 42. ↩

-

Floyd 1999, p. 60. ↩

-

Floyd 1999, p. 57. ↩

-

Floyd 1999, p. 61. ↩

-

Floyd 1999, p. 95. ↩

-

Floyd 1999, p. 103. ↩

-

Floyd 1999, p. 123. ↩

-

Floyd 1999, p. 127. ↩

-

Hintz 1999, p. 1. ↩

-

Lefebvre & Muysken 1998, p. 89. ↩

-

Aikhenvald 2004, p. 68-69. ↩

-

Weber 1986, p. 145. ↩

-

Floyd 1999, p. 87. ↩

-

Floyd 1999, p. 89. ↩

-

Aikhenvald 2004, p. 72. ↩

-

Aikhenvald 2004, p. 79. ↩

-

Aikhenvald 2004, p. 358. ↩

-

Aikhenvald 2004, p. 380. ↩

-

“History”. Homepage.ntlworld.com. Archived from the original on 2013-05-15. Retrieved 2012-11-09. ↩

-

López Lamerain, Constanza (2011). “El iii concilio de lima y la conformación de una normativa evangelizadora para la provincia eclesiástica del perãš”. Intus-Legere Historia. 5 (2): 51–58. doi:10.15691/07198949.90 (inactive 1 November 2024). ISSN 0719-8949.

{{[cite journal](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Template:Cite_journal "Template:Cite journal")}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) ↩ -

Saenz, S. Dedenbach-Salazar. 1990. Quechua Sprachmaterialen. In: Meyers, A., M. Volland. Beiträge zur Kulturgeschichte des westlichen Südamerika. Forschungsberichte des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen. P. 258. ↩

-

Carnival Theater: Uruguay’s Popular Performers and National Culture ↩

-

“Demetrio Túpac Yupanqui, el traductor al quechua de ‘El Quijote’, muere a los 94 años”. El País. 2018-05-04. Retrieved 2019-10-28. ↩

-

Collyns, Dan (2016-12-14). “Peru airs news in Quechua, indigenous language of Inca empire, for first time”. The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2024-05-26. Retrieved 2019-10-28. ↩

-

“Peru: The State of Quechua on the Internet · Global Voices”. Global Voices. 2011-09-09. Retrieved 2017-01-02. ↩

-

“Film Kukuli (Cuzco-Peru)“. Latinos in London. 18 November 2011. Retrieved 2012-11-10. ↩

-

Hutchinson, Sean (8 December 2015). “‘Star Wars’ Languages Owe to Tibetan, Finnish, Haya, Quechua, and Penguins”. Inverse. Archived from the original on 2023-01-15. Retrieved 2022-04-10. ↩