Contents

Much of deep learning still boils down to alchemy, but understanding and optimizing the performance of your models doesn’t have to — even at huge scale! Relatively simple principles apply everywhere — from dealing with a single accelerator to tens of thousands — and understanding them lets you do many useful things:

- Ballpark how close parts of your model are to their theoretical optimum.

- Make informed choices about different parallelism schemes at different scales (how you split the computation across multiple devices).

- Estimate the cost and time required to train and run large Transformer models.

- Design algorithms that take advantage of specific hardware affordances.

- Design hardware driven by an explicit understanding of what limits current algorithm performance.

Expected background: We’re going to assume you have a basic understanding of LLMs and the Transformer architecture but not necessarily how they operate at scale. You should know the basics of LLM training and ideally have some basic familiarity with JAX. Some useful background reading might include this blog post on the Transformer architecture and these excellent slides on LLM scaling in JAX.

Goals & Feedback: By the end, you should feel comfortable estimating the best parallelism scheme for a Transformer model on a given hardware platform, and roughly how long training and inference should take. If you don’t, message us! We’d love to know how we could make this clearer.

Why should you care?

Three or four years ago, I don’t think most ML researchers would have needed to understand any of this. But today even “small” models run so close to hardware limits that doing novel research requires you to think about efficiency at scale.Historically, ML research has followed something of a tick-tock cycle between systems innovations and software improvements. Alex Krizhevsky had to write unholy CUDA code to make CNNs fast but within a couple years, libraries like Theano and TensorFlow meant you didn’t have to. Maybe that will happen here too and everything in this book will be abstracted away in a few years. But scaling laws have pushed our models perpetually to the very frontier of our hardware, and it seems likely that, in the near future, doing cutting edge research will be inextricably tied to an understanding of how to efficiently scale models to large hardware topologies. A 20% win on benchmarks is irrelevant if it comes at a 20% cost to roofline efficiency. Promising model architectures routinely fail either because they can’t run efficiently at scale or because no one puts in the work to make them do so.

The goal of “model scaling” is to be able to increase the number of chips used for training or inference while achieving a proportional, linear increase in throughput. This is known as “strong scaling”. Although adding additional chips (“parallelism”) usually decreases the computation time, it also comes at the cost of added communication between chips. When communication takes longer than computation we become “communication bound” and cannot scale strongly.As your computation time decreases, you also typically face bottlenecks at the level of a single chip. Your shiny new TPU or GPU may be rated to perform 500 trillion operations-per-second, but if you aren’t careful it can just as easily do a tenth of that if it’s bogged down moving parameters around in memory. The interplay of per-chip computation, memory bandwidth, and total memory is critical to the scaling story. If we understand our hardware well enough to anticipate where these bottlenecks will arise, we can design or reconfigure our models to avoid them.Hardware designers face the inverse problem: building hardware that provides just enough compute, bandwidth, and memory for our algorithms while minimizing cost. You can imagine how stressful this “co-design” problem is: you have to bet on what algorithms will look like when the first chips actually become available, often 2 to 3 years down the road. The story of the TPU is a resounding success in this game. Matrix multiplication is a unique algorithm in the sense that it uses far more FLOPs per byte of memory than almost any other (N FLOPs per byte), and early TPUs and their systolic array architecture achieved far better perf / $ than GPUs did at the time they were built. TPUs were designed for ML workloads, and GPUs with their TensorCores are rapidly changing to fill this niche as well. But you can imagine how costly it would have been if neural networks had not taken off, or had changed in some fundamental way that TPUs (which are inherently less flexible than GPUs) could not handle.

Our goal in this book is to explain how TPU (and GPU) hardware works and how the Transformer architecture has evolved to perform well on current hardware. We hope this will be useful both for researchers designing new architectures and for engineers working to make the current generation of LLMs run fast.

High-Level Outline

The overall structure of this book is as follows:

Section 1 explains roofline analysis and what factors can limit our ability to scale (communication, computation, and memory). Section 2 and Section 3 talk in detail about how TPUs and modern GPUs work, both as individual chips and — of critical importance — as an interconnected system with inter-chip links of limited bandwidth and latency. We’ll answer questions like:

- How long should a matrix multiply of a certain size take? At what point is it bound by compute or by memory or communication bandwidth?

- How are TPUs wired together to form training clusters? How much bandwidth does each part of the system have?

- How long does it take to gather, scatter, or re-distribute arrays across multiple TPUs?

- How do we efficiently multiply matrices that are distributed differently across devices?

Figure: a diagram from Section 2 showing how a TPU performs an elementwise product. Depending on the size of our arrays and the bandwidth of various links, we can find ourselves compute-bound (using the full hardware compute capacity) or comms-bound (bottlenecked by memory loading).

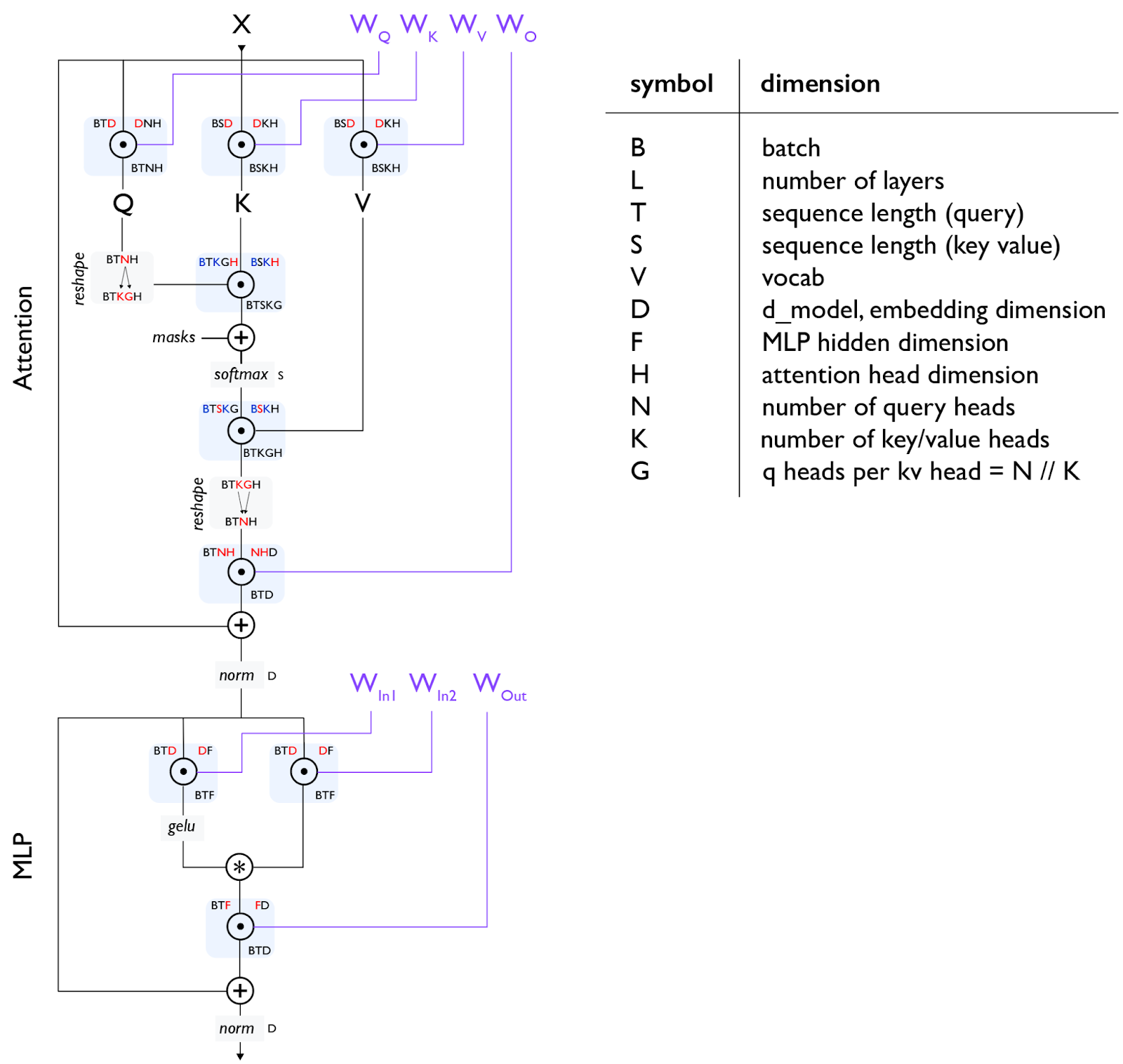

Five years ago ML had a colorful landscape of architectures — ConvNets, LSTMs, MLPs, Transformers — but now we mostly just have the Transformer. We strongly believe it’s worth understanding every piece of the Transformer architecture: the exact sizes of every matrix, where normalization occurs, how many parameters and FLOPsFLoating point OPs, basically the total number of adds and multiplies required. While many sources take FLOPs to mean “operations per second”, we use FLOPs/s to indicate that explicitly. are in each part. Section 4 goes through this “Transformer math” carefully, showing how to count the parameters and FLOPs for both training and inference. This tells us how much memory our model will use, how much time we’ll spend on compute or comms, and when attention will become important relative to the feed-forward blocks.

Figure: a standard Transformer layer with each matrix multiplication (matmul) shown as a dot inside a circle. All parameters (excluding norms) are shown in purple. Section 4 walks through this diagram in more detail.

Section 5: Training and Section 7: Inference are the core of this essay, where we discuss the fundamental question: given a model of some size and some number of chips, how do I parallelize my model to stay in the “strong scaling” regime? This is a simple question with a surprisingly complicated answer. At a high level, there are 4 primary parallelism techniques used to split models over multiple chips (data, tensor, pipeline and expert), and a number of other techniques to reduce the memory requirements (rematerialisation, optimizer/model sharding (aka ZeRO), host offload, gradient accumulation). We discuss many of these here.

We hope by the end of these sections you should be able to choose among them yourself for new architectures or settings. Section 6 and Section 8 are practical tutorials that apply these concepts to LLaMA-3, a popular open-source model.

Finally, Section 9 and Section 10 look at how to implement some of these ideas in JAX and how to profile and debug your code when things go wrong.

Throughout we try to give you problems to work for yourself. Please feel no pressure to read all the sections or read them in order. And please leave feedback. For the time being, this is a draft and will continue to be revised. Thank you!

We’d like to acknowledge James Bradbury and Blake Hechtman who derived many of the ideas in this doc.

Without further ado, here is Section 1 about TPU rooflines.

Links to Sections

This series is probably longer than it needs to be, but we hope that won’t deter you. The first three chapters are preliminaries and can be skipped if familiar, although they introduce notation used later. The final three parts might be the most practically useful, since they explain how to work with real models.

Part 1: Preliminaries

- Chapter 1: A Brief Intro to Roofline Analysis. Algorithms are bounded by three things: compute, communication, and memory. We can use these to approximate how fast our algorithms will run.

- Chapter 2: How to Think About TPUs. How do TPUs work? How does that affect what models we can train and serve?

- Chapter 3: Sharded Matrices and How to Multiply Them. Here we explain model sharding and multi-TPU parallelism by way of our favorite operation: (sharded) matrix multiplications.

Part 2: Transformers

- Chapter 4: All the Transformer Math You Need to Know. How many FLOPs does a Transformer use in its forward and backwards pass? Can you calculate the number of parameters? The size of its KV caches? We work through this math here.

- Chapter 5: How to Parallelize a Transformer for Training. FSDP. Megatron sharding. Pipeline parallelism. Given some number of chips, how do I train a model of a given size with a given batch size as efficiently as possible?

- Chapter 6: Training LLaMA 3 on TPUs. How would we train LLaMA 3 on TPUs? How long would it take? How much would it cost?

- Chapter 7: All About Transformer Inference. Once we’ve trained a model, we have to serve it. Inference adds a new consideration — latency — and changes up the memory landscape. We’ll talk about how disaggregated serving works and how to think about KV caches.

- Chapter 8: Serving LLaMA 3 on TPUs. How much would it cost to serve LLaMA 3 on TPU v5e? What are the latency/throughput tradeoffs?

Part 3: Practical Tutorials

- Chapter 9: How to Profile TPU Code. Real LLMs are never as simple as the theory above. Here we explain the JAX + XLA stack and how to use the JAX/TensorBoard profiler to debug and fix real issues.

- Chapter 10: Programming TPUs in JAX. JAX provides a bunch of magical APIs for parallelizing computation, but you need to know how to use them. Fun examples and worked problems.

- Chapter 11: Conclusions and Further Reading. Closing thoughts and further reading on TPUs and LLMs.